New Resource for Implementing Amendments 24-A and C

Recent amendments to the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)'s Book of Order take effect July 4, 2025, following ratification by a majority of the denomination's presbyteries. To support implementation, the Covenant Network of Presbyterians has published a practical guide for presbyteries and sessions.

Celebrating Pride Month with Featured Resources

Happy Pride month! This June, CNP is highlighting specific resources to help you and your congregation engage meaningfully in Pride celebrations and ministry to LGBTQIA+ neighbors.

Covenant Network of Presbyterians Celebrates Presbyteries' Approval of Amendment 24-C, Another Historic Step for Inclusion

Amendment 24-C ensures that the PC(USA)’s commitment to inclusion and diversity will play a more substantial role in decision-making about ordination and installation of ministers, elders and deacons.

Applications Open for Covenant Fellows Program

CNP is excited to launch a new Covenant Fellows Program designed to cultivate the next generation of church leaders committed to LGBTQIA+ inclusion and advocacy within the PC(USA).

Resources for Transgender Day of Visibility

The Covenant Network of Presbyterians offers several resources for congregations seeking to better understand and support transgender and non-binary siblings in Christ.

Welcome to CNP’s New Website

The Covenant Network of Presbyterians has just launched a redesigned website with improved functionality and accessibility. This updated website provides easier access than ever to resources that equip, engage and empower congregations to welcome all people of God.

CNP Celebrates Presbyteries’ Approval of Amendment 24-A, Recognizing LGBTQIA+ People in Church Constitution

The Covenant Network of Presbyterians rejoices in the ratification of Amendment 24-A enshrining, for the first time, recognition of LGBTQIA+ people in the Constitution of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Proposed Amendments 24-A and 24-C

Presbyteries are currently voting on two amendments to the Book of Order that were approved by wide margins by the General Assembly in July 2024. Here’s some help understanding the impact and importance of these amendments.

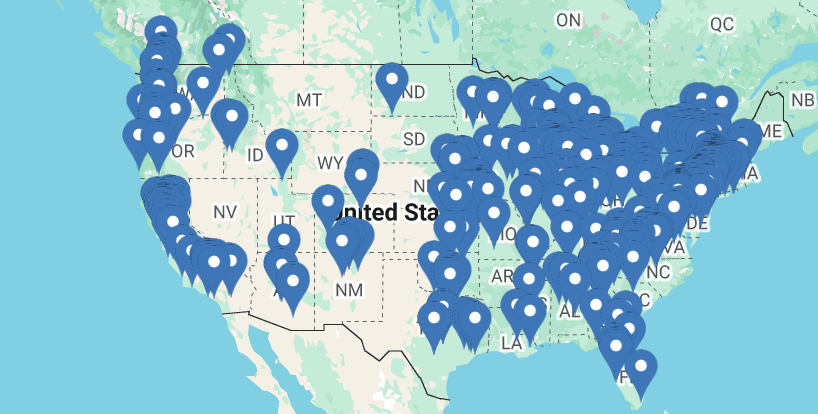

Tracking PC(USA) Constitutional Amendments 24-A and 24-C

Help update this tracker by reporting updates to us. Please include presbytery name, date of vote and results.

CNP Board Responds to Federal Government Actions Affecting Trans and Non-binary Persons, Calls for PCUSA Action

The Board of Directors of the Covenant Network of Presbyterians offers the following call in response to the federal government’s actions of the past three weeks as they affect transgender and non-binary people:

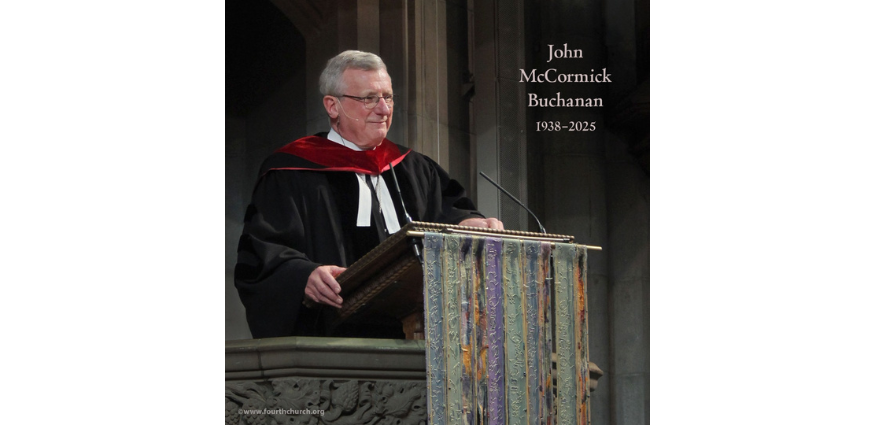

Remembering John Buchanan

The Covenant Network of Presbyterians is giving thanks for the life and faith of its Founding Co-Moderator of the Board of Directors, the Rev. Dr. John M. Buchanan. Buchanan was longtime pastor of Fourth Presbyterian Church in Chicago and Moderator of the 208th General Assembly (1996).

Connecting with CNP at the APCE Annual Event

At APCE’s 2025 Annual Event, CNP is offering two workshops equipping and empowering churches to welcome all God’s people.